What’s the Earliest Evidence for Christianity? (The Answer Might Surprise You)

What is the earliest historical proof of the existence of Christianity?

Today, almost all scholars in the fields of ancient history, classics, and biblical studies, regardless of their religious beliefs, agree on some fundamental facts about Jesus of Nazareth. For example, Jesus started his public ministry after being baptized by John the Baptist. He was known for performing miracles and driving out demons. He was crucified under Pontius Pilate during the reign of Tiberius Caesar. After his death, many of his followers, including Paul who was once his opponent, began to proclaim in Jerusalem that Jesus had appeared to them alive, resurrected from the dead. These are undeniable historical facts.

How do we know these (or any) historical facts about Jesus and early Christianity? Mainly from the New Testament documents written in the first century AD. But how closely can these sources bring us to the real Jesus of Nazareth? In other words, what is the earliest historical evidence for Christianity? The answer might shock you.

Getting Closer to the Core Evidence

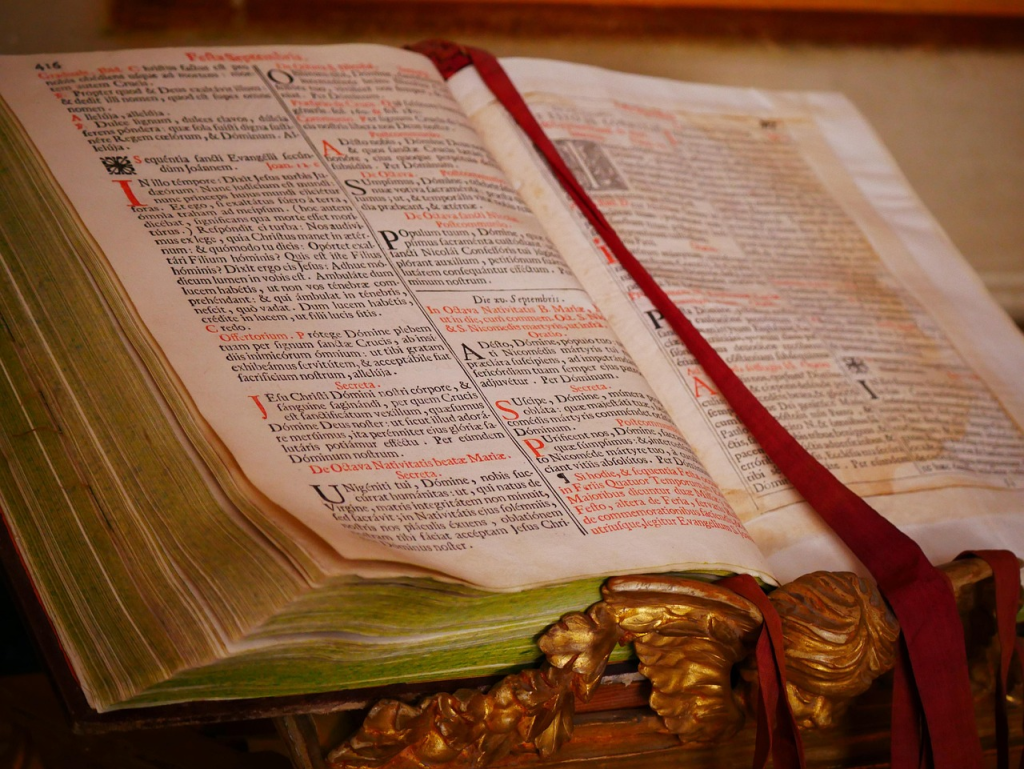

Some of the oldest evidence for Christianity comes from manuscripts like Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus, which date back to the early fourth century AD. Constantin von Tischendorf, often compared to Indiana Jones in the world of New Testament manuscripts, found Sinaiticus at St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt in 1859. He later recounted that he saved Sinaiticus from being burned by monks who had already thrown two piles of similar manuscripts into the fire! Tischendorf went on to call Sinaiticus “the most precious biblical treasure in existence.”

Then there are the papyrus manuscripts, many of which are older than Sinaiticus. One of the earliest is P52, a small three – inch piece of papyrus with five verses from the Gospel of John (18:31–33, 37–38). Currently, it is dated between AD 125–175, though some suggest a wider time range.

However, followers of Jesus should be aware of another groundbreaking discovery that, in my opinion, is more significant than Sinaiticus, more important than P52, and even more crucial than all archaeological discoveries combined: the discovery of the pre – Pauline creedal tradition in 1 Corinthians 15:3–7. This has rightfully been called the “pearl of great price.”

This apostolic creedal statement is unique in the New Testament and indeed in all of ancient literature. Even if only this five – verse creedal tradition had survived from the early Christian movement, we would still have the essence of the gospel and the historical foundation of Christianity: “This Jesus God raised up again, to which we are all witnesses” (Acts 2:32).

Uncovering Christianity’s Historical Foundation

Let’s take a look at the earliest evidence for Christianity:

- Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures.

- He was buried.

- He was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures.

- He appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve.

- Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers at once.

- Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles.

The above is what scholars believe to be the actual creedal tradition that Paul received, without his additional words and comments. This is a relatively new discovery. Even the New Testament scholar (and atheist) Gerd Lüdemann called this discovery “one of the great achievements of recent New Testament scholarship.” The early Church Fathers, medieval theologians, and reformers were all familiar with, quoted, and commented on 1 Corinthians 15:3–7. But it wasn’t until the early 20th century that people realized it wasn’t originally written by Paul. Instead, it was a creedal tradition that Paul had received more than a decade before AD 49 or 50, when he established the Corinthian church.

Even New Testament scholar (and atheist) Gerd Lüdemann calls this discovery ‘one of the great achievements of recent New Testament scholarship.’

There are two main reasons, found within the biblical text itself, that support this conclusion.

First, Paul introduces it with the words “delivered” and “received” (1 Cor. 15:3). When Paul founded the church in Corinth, he passed on certain traditions to the Corinthians to further explain the gospel (cf. 1 Cor. 11:2) that he himself had received. These included teachings and stories about Jesus (1 Cor. 7:10; 9:14; 11:1; 2 Cor. 10:1), the account of the Lord’s Supper (1 Cor. 11:23–26), hymns (1 Cor. 8:6; 2 Cor. 8:9), and this creedal tradition about Jesus’s death, burial, resurrection, and appearances (1 Cor. 15:3–7).

The second major reason is linguistic. Paul uses words and phrases here that he doesn’t use anywhere else. Phrases like “died for our sins,” “in accordance with the Scriptures,” “he was buried,” “he was raised,” “on the third day,” “he appeared,” and “the twelve” are either only used in this passage or, if used elsewhere, are clearly influenced by this tradition.

These factors have convinced almost all scholars that 1 Corinthians 15:3–7 is a pre – Pauline creedal tradition. It predates Paul’s earliest letters. But just how early is it?

When and Where Did Paul Receive This Tradition?

When looking at the academic literature, scholars from various backgrounds and beliefs (or lack of beliefs) mostly agree that this creedal tradition, on average, dates back to within five years of Jesus’s death. Some argue it was around a decade after, and some even suggest it was within a year. For example, New Testament scholar James Dunn argues, “This tradition, we can be entirely confident, was formulated as tradition within months of Jesus’s death.”

Scholars from all different backgrounds . . . are virtually unanimous that this creedal tradition dates, on average, to within five years of Jesus’s death.

I think Dunn’s estimate is the most accurate. Just “months” after Jesus’s crucifixion, new converts were likely learning and memorizing this creedal formula, perhaps during the church – planting efforts of the apostles and their disciples. It may have served as the basis for an introductory religious instruction for new believers. Additionally, 1 Corinthians 15:3–7 is the creedal summary and foundation for the sermons in Acts (see Acts 10:39–40; 13:28–31) and the Passion narratives in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

Where, when, and from whom did Paul receive this precious creedal tradition? Scholars believe it was either soon after his conversion in Damascus (AD 34) or three years later in Jerusalem (AD 37), when he spent two weeks with Peter (Gal. 1:18) and also met James, Jesus’s brother (Gal. 1:19). I prefer the latter option. It better explains how he got information such as “[the risen Christ] appeared to Cephas . . . [and] to James” (1 Cor. 15:5, 7). New Testament scholar and agnostic Bart Ehrman agrees: “This visit is one of the most likely places where Paul learned all the received traditions that he refers to and even the received traditions that we otherwise suspect are in his writings that he does not name as such.”

Christians Should Take a Stand

The most ancient source and earliest evidence for Christianity is not only a solid foundation for Jesus followers but also a powerful argument for engaging with 21st – century non – believers. In the AD 30s, the earliest followers of Jesus were proclaiming that Jesus died on the cross for their sins and rose from the dead as the Lord of the world. Jesus’s brother James, his chief apostle Peter, and his former enemy Paul all claimed that the resurrected Jesus had appeared to them. The fact that these three men believed this is historically undeniable (see 1 Cor. 15:11). Moreover, the historical evidence that these three men were martyred for their faith is strong enough to persuade skeptics like Ehrman. Whatever they saw was clearly so significant that they were willing to sacrifice their lives for it.

Whatever Peter, James, and Paul saw, it was worth giving their lives for.

Furthermore, according to this ancient source, the twelve apostles and even more than 500 people claimed to have seen Jesus. Two thousand years later, billions of people from Jerusalem to Papua New Guinea still believe they have encountered the risen Jesus through faith. As A. N. Wilson, a former skeptic who became a Christian because of the resurrection, wrote: “J. S. Bach believed the story, and set it to music. Most of the greatest writers and thinkers of the past 1,500 years have believed it.”

May we go out into the non – believing world, firmly standing on the historical foundation of 1 Corinthians 15:3–7, and gently ask for an answer: What is this power that transformed the lives of the apostles, turned the Roman Empire on its head, and changed the course of human history and the lives of billions to this day? Who or what did they see?