Seeds of Religious Freedom: Commemorating the 500th Anniversary of the Anabaptist Movement

On January 21, 1525, as snow blanketed the narrow streets of Zurich, a group of young Swiss reformers gathered secretly inside Felix Manz’s home, which was in the shadow of the Grossmünster cathedral. The frigid air outside contrasted sharply with the passionate prayers and intense discussions filling the room. This gathering was illegal; Zurich’s city council had explicitly prohibited these men from coming together for Bible study.

Despite the council’s edict, the seeds of religious freedom had already been sown. By the end of that fateful night, the first believers’ church of the Reformation era came into existence.

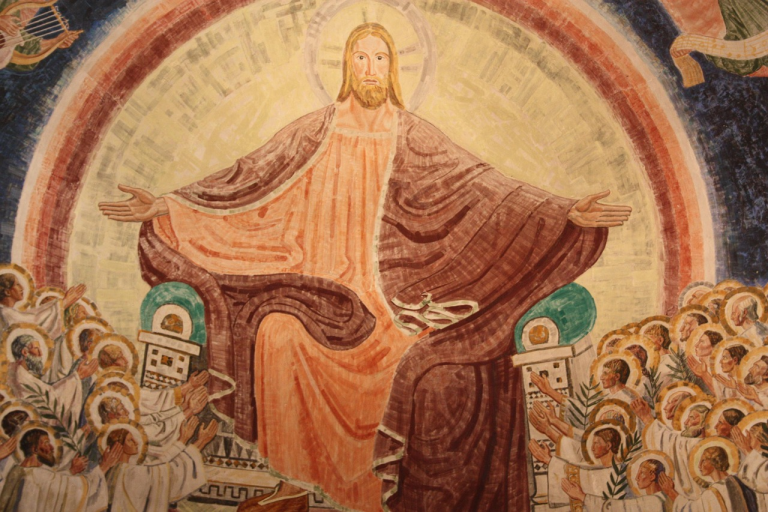

Taking the Reformation to New Depths

A few days prior, the group’s former teacher, Huldrych Zwingli – a well – known biblical scholar, humanist, and Protestant reformer – had publicly debated his disillusioned students on the matter of infant baptism. As the people’s priest at the Grossmünster, Zwingli was a magisterial reformer. He had the support of the city council’s legal authority to implement changes in the Zurich church. The three leaders of the January 21 meeting – Conrad Grebel, Felix Manz, and George Blaurock – had made compelling arguments in favor of believer’s baptism. However, the council sided with Zwingli, ordering his opponents to disperse. To add insult to injury, all unbaptized infants were now legally required to be baptized. Grebel, who had an infant daughter, firmly believed that councils should not have power over the church.

Ironically, it was Zwingli who had taught Grebel, his former protégé and close friend, to reform the church strictly in line with the Bible. Proficient in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, Zwingli had assembled a group of young intellectuals around him to study biblical languages and Greek classics. Grebel, hailing from a prominent local family and having studied in Paris before returning to Zurich, was introduced to the Greek New Testament and the meaning of “baptizō,” the Greek word for “baptize,” by Zwingli.

By 1522, Zwingli began to concur with his enthusiastic students that the Catholic Mass should be abolished and religious images removed from public worship. However, after arguing against these practices, he often gave in to the council’s decision to keep them. From the pulpit, Zwingli preached about biblical authority and the need for church reform. But his actions showed a desire for local government approval. By late 1524, Zwingli’s students felt betrayed by the man who had taught them not to compromise when Scripture was clear. In their eyes, the Reformation had not gone far enough.

A Pivotal and Historic Decision

An eyewitness to the historic meeting (likely Blaurock) later recounted in The Large Chronicle of the Hutterian Brethren, “It came to pass that they were together until anxiety came upon them, yes, and they were so pressed within their hearts. Thereupon they began to bow their knees to the Most High God in heaven and called upon him as the Informer of Hearts.”

After seeking divine guidance through prayer, they made a crucial and epoch – making decision to establish believer’s baptism. Since there was no ordained minister present to perform the baptism, young Grebel took a handful of water and baptized his friend Blaurock. In return, Blaurock baptized Grebel, Manz, and the other men in the room. With this radical step, these “Swiss Brethren,” as they would later be known, launched the Anabaptist movement.

The following week, after preaching in the nearby town of Zollikon, Grebel and his companions sparked a small revival, attracting numerous followers to the Anabaptist cause. Over the next century, Anabaptists experienced significant growth, despite facing severe persecution.

Two years after their momentous meeting in Zurich, the Anabaptist movement had developed enough to create the Schleitheim Confession. This confession not only rejected war but also lawsuits and oaths. Theologians like Balthasar Hübmaier soon published treatises defending religious liberty and opposing infant baptism, but at great personal risk. When Hübmaier fled to Zurich in 1528, he was eventually tortured and sent to Vienna, where he was burned in the public square. His wife was drowned.

A Legacy of Martyrdom, Pacifism, and Religious Liberty

Compared to other Reformation – era traditions, the Anabaptists did not produce many significant systematic theologians. The main reason was their short – lived existence.

Less than a year and a half after instituting believer’s baptism, Grebel, whom Zwingli had once called the “Coryphaeus of the movement,” died of the plague. Manz, the “Apollo” of the group, was drowned in 1527, becoming the first Anabaptist martyr. Blaurock, the “Hercules” of the early Anabaptists whose ministry was more extensive than his friends’, was burned at the stake in 1529. One historian has speculated that more Anabaptists were martyred by fellow Christians in the 16th century than Christians were martyred by the Romans in the first three centuries of the church.

Although events like the violent and chaotic Münster rebellion and figures like the Zwickau prophets have sometimes led to the Anabaptists being labeled “radical reformers,” they were best known to their contemporaries (just as their descendants, the Amish and Mennonites, are today) for their extreme pacifism. This was exemplified by the writings of Menno Simons (1496 – 1561), the most influential Anabaptist writer.

On the 500th anniversary of the meeting of Grebel, Manz, Blaurock, and others in Zurich, perhaps the most enduring legacy of the Anabaptists today is their dedication to an early form of religious liberty. This was an idea that the major Protestant reformers did not champion, despite their many achievements for the church. The Grebel circle’s “Letter to Thomas Müntzer” in 1524 is now recognized as “the earliest document of the Protestant free church.”

While later Baptists have distanced themselves from the “mad men of Münster,” and early Anabaptists did not always practice baptism by immersion like modern – day Baptists, every American Christian owes a debt to the small group of men in Zurich in 1525. They advocated – even when it was unpopular – that the church should be subject to God’s Word, not to the decisions of human councils.